Durham Cathedral; discover this magnificent cathedral, its treasures, St Cuthbert, the Venerable Bede and the Anglo-Saxon World.

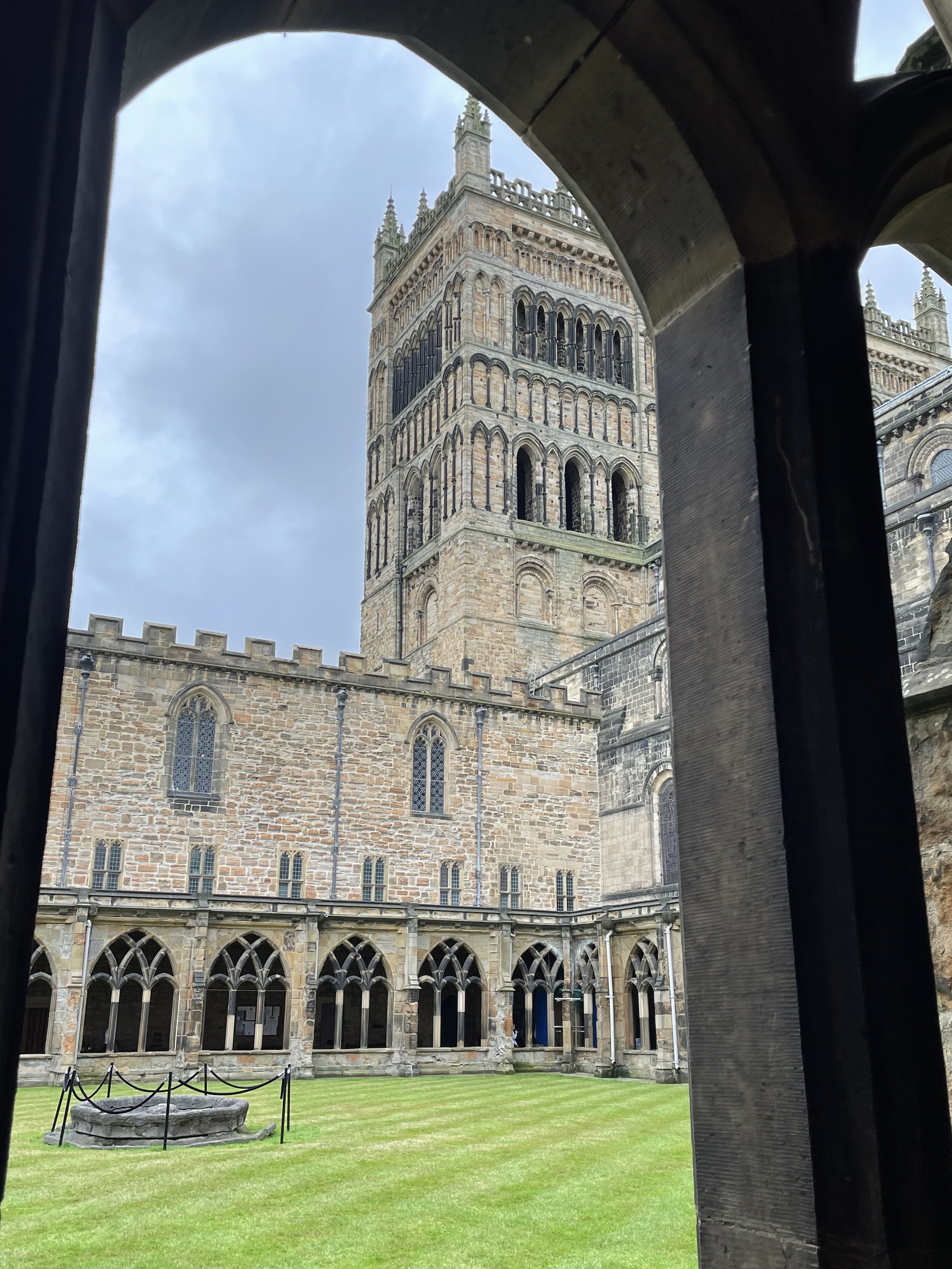

/Durham Cathedral is a very special building for a number of reasons to the extent that the author, Bill Bryson wrote it was “the best cathedral on Planet Earth.”Building began in 1093 and was to take 40 years to complete. This makes it a staggering 890 years old and is still functioning every day of the year. It is a good example of Romanesque architecture with its rounded or semi-circular arches, typical of architecture under the Normans (Norman castles have these arches too). When built it was Britain’s tallest building and must have amazed onlookers at a time when buildings were mainly made out of wood with wattle and daub walls and a thatched roof. It shares its position on a promontory occupying a bend in the River Weir, with Durham Castle and, together, gives the impression of Norman power to all who saw them. The river, covering three sides of the promontory acts as a natural moat which makes it a natural stronghold in the face of marauding Scots, Vikings and any rebellious Anglo-Saxons. Added to this the spiritual leader based here was given the title “Prince Bishop”, giving him far more secular powers than an ordinary bishop and even allowing him to raise an army and mint money! The Prince Bishop’s coins would even have their own image on one side instead of the monarchs. It is also the last resting place of St Cuthbert whose shrine became one of the earliest places in Britain to develop massed pilgrimages. People would walk from far and wide to ask for help from St Cuthbert. It is also home to a shrine to “The Venerable Bede”, (673-735AD) who wrote “The Ecclesiastical History of the English People” and as a consequence is known as the “Father of English History”. Anyone who has studied the Anglo-Saxons will have read his book or sections of it, as I had to do back in the early 1970s!

Durham Castle that shares the promontory with the Cathedral.

Straightaway, we can see the building is full of those Romanesque/Norman arches, although the two large windows on the left are from a later period.

As you wander up to the entrance, you will notice the Norman arched entrance and this time marked with chevrons, another Norman decoration on arches both in churches and castles.

Before entering have a look at the impressive door knocker with a special function. When the Cathedral was part of a monastery ie before Henry shut them down in 1536, anyone accused of breaking the law could run to the Cathedral before getting caught, bang on the door with the knocker and ask the monks for “Sanctuary”. This meant he could not be arrested whilst inside the Cathedral. The accused would have 37 days to make peace with the pursuing authorities or be banished from England for ever. This practice was still in effect until James I banned it. The knocker in this photo is an exact copy but the real one is preserved upstairs in the museum.

Above; Having entered the Cathedral, your route takes you into the Galilee Chapel. More Norman arches and chevrons are apparent but if you look at the the wall above the arches, some faint paintings can be seen. A closeup of which can be seen in the photo below.

Above; the pink arrows point out paintings are of various apostles being executed, sacrificing themselves rather than renouncing or rejecting their faith. The last one on the right is showing St Peter being crucified upside down. Emperor Nero blamed St Peter and other Christians for the fire that destroyed a lot of Rome. Peter asked that he should be crucified upside down because he felt unworthy to die in the same manner as Christ.

Below; a close up of St Peter’s crucifixion.

Above; the Galilee Chapel where the Venerable Bede’s shrine is located.

Above and below; the shrine of the St Bede aka “The Venerable Bede.

The Venerable Bede can be seen as a polymath, an expert on loads of things. He was born in about 673 AD near Wearmouth, Northumberland and died in the monastery at nearby Jarrow. He was educated as a novice monk at Wearmouth Monastery from the age of seven and later moved to the newly created monastery of Jarrow and it was here, that he gained a world-wide reputation. Unlike many other saints who gain their reputations from deeds done during their travels, Bede was famous for his studies in Jarrow’s large library. He wrote or translated 40 books on religion, science, astronomy, mathematics, history and language. On his deathbed he continued to work making sure he completed his translation of the Gospel of St John by dictating to a scribe. In astronomy, he stated the world was round when the accepted view was that it was flat. His most famous work was The Ecclesiastical History of England written in 731and was comprised of five books. You can still buy a modern translated copy from Amazon and other booksellers. Bede takes the reader back to Julius Caesar’s invasion of England in 55BC, the martyrdom of St Alban and Augustine’s mission England in 597 AD to convert the English to Christianity. He includes numerous events right up to 731 including Christianity versus paganism and the triumph of Roman christianity over christianity that came over from Ireland. It is a valuable source for historian’s studying Early English History although has numerous errors which are only to be expected when considering the large period of time that it covers and the scarceness of source material for Bede to base his writing on.

How did he come to be buried in Durham and not Jarrow? Legend has it that he was buried near St Cuthbert on Lindisfarne but when St Cuthbert’s body was exhumed, somebody put Bede’s bones in a bag and sneaked it into St Cuthbert’s coffin. It was later buried in Durham with St Cuthbert but in 1104, when St Cuthbert was moved to his new shrine in the newly built cathedral, Bede’s relics were rediscovered and buried nearby. In 1370, Bede was moved to his own shrine in the Galilee Chapel.

A medieval wall painting of St Cuthbert.

Above and below; Walking along the nave there is a series of beautiful Norman drum piers or columns with numerous geometric designs chiselled out. Note too, more round arches either side and in the foreground, whereas in the distance there are pointed arches.

Below; looking up inside the tower.

Above; Durham’s amazing ribbed vaulting.

Above; looking through the “Quire”

Above; I am always looking for a Green Man in churches and cathedrals and in this case, a very helpful guide pointed this one out.

At the top of this photo is the “Bishop’s throne or “cathedra”. It I can be interpreted as a symbol of Bishop Hatfield’s ego because he wanted a throne taller than the Pope’s throne in the Vatican. To make certain it would be higher, he even sent men to Rome to measure the Pope’s throne and on their return, it was built one inch higher. His throne became the highest throne in Christendom and it has never been beaten. Allegedly, the Pope got his own back by having an extra thick cushion made to raise him even higher! Today it is considered too “over the top” and so the current bishop sits at the ground floor level. Apparently, Hatfield had a good sense of humour and said, “the next bishop of Durham will be enthroned over my dead body!”

Above, Edward III (1327-77)with his coat of arms. In 1340 his coat of arms changed to include the “fleurs-de-lis”, which stated that he claimed the French crown too. Bishop Hatfield was a great friend of Edward III with both men fighting and defeating the French, at the Battle of Crecy in 1346. During the battle, the Black Prince got into difficulty and it was Hatfield who was asked by Edward to take some men and rescue his son. In gratitude, Hatfield was given all kinds of gifts which included, when the Bishop asked if he could have the royal coat of arms and a depiction of the king on his tomb, it was granted. This is unique in being the only non royal tomb with these accompaniments.

The “High altar” and behind it, the “Neville screen. Originally, the cathedral was built as a monument to St Cuthbert and consequently, nobody else was allowed to buried inside it. However, in the 14th century, the rules were changed for the powerful Neville family and hence the Neville screen was built. This was originally painted in bright colours and on each stand, two of which are arrowed, were statues of angels and saints. When the “Reformation” took place under Henry VIII and his son, Edward VI, all 107 alabaster statues were taken down and hidden by monks to prevent them being destroyed. The monks had only three days warning of what was to happen and so had little time to prepare for this dreadful event. Unfortunately, over time the location of the hiding place was forgotten and they have yet to be rediscovered! To make matters worse, experts predict that if they had been crated they would disintegrate when the crate is opened.

Below; The Shrine of St Cuthbert. St Cuthbert is sometimes known as the patron saint of Northern England and some people even refer to him as England’s greatest saint. His shrine at Durham quickly became one of the first sites of mass pilgrimage. People came from all over the country to ask St Cuthbert for help and they brought to Durham a huge income.

As a young shepherd, in 651 AD he had a vision of God which drew him into becoming a Benedictine monk in Melrose. Ten years later plague came to Melrose and so Cuthbert devoted himself to helping plague victims as well as teaching people about the christian message. His work, apparently, resulted in several miracles which put him on the road to sainthood. He became the prior at Melrose and in 664 became the prior at Lindisfarne aka today, Holy Island. In 676, he retired to become a “hermit” on an island called the Inner Farne. Devoting his life to prayer, isolation and austerity, his fame grew across Northumbria. For a short period he was persuaded to come out of retirement to become Bishop of Lindisfarne but soon went back to the isolated life of a hermit. He has also been attributed developing powers of healing and prophesy. He died in 687 AD and was buried on Lindisfarne. Eleven years later, it was decided to rebury him in the church on Lisfarne but when he was removed from the earth, amazingly it was observed that his body had not decomposed. Another exhumation then took place after the infamous Viking raid of 875 AD to protect his holy remains. All this time people had been praying to Saint Cuthbert to intercede with God and apparently numerous miracles followed. His body was now taken to the mainland for safe keeping and moved around until 995 AD on a cart from place to place to avoid the Vikings and the Scots. However, according to legend, when the cart became stuck and was immovable, it was taken to be a sign that St Cuthbert had chosen his last resting place. This was to be the location of Durham Cathedral.

A small Saxon church was built to house the Shrine of St Cuthbert and in 1104, Cuthbert’s body was place in the newly built cathedral, then part of a Benedictine monastery. When the body was disinterred, once again, legend has it that miraculously, it showed no signs of decay. Being a monastery, by 1537 and Henry VIII’s Reformation, it became part of the “Dissolution of the Monasteries” and was forced to close. Henry’s commissioners took away all the gold and jewels associated with Cuthbert’s shrine but when they began to remove the body, apparently, yet again, his body had not decayed! The story goes on to state that they were so amazed that they allowed the body and shrine to remain and proclaimed that the Cathedral would not be destroyed. If you would like to know what could have happened, visit the ruins of Rivaulx Abbey or Fountains Abbey. These are stunning ruins but definitely ruins.

Above; a statue of a headless St Cuthbert carrying King Oswald’s head. England in the 7th century was made up of several kingdoms, one of which was Northumbria. The Northumbrian King Oswald, the man who helped to bring christianity to Northumbria was killed in the Battle of Maserfield in 641 or 642. According to Bede, Oswald’s head, hands and arms were cut off and placed on stakes on the orders of King Panda of Mercia. Oswald’s successor, King Oswiu succeeded in obtaining Oswald’s remains and sent his head to Lindisfarne to be safe and treated as holy relics. When Cuthbert’s remains were removed from Lindisfarne, Oswald’s head was placed in Cuthbert’s coffin and subsequently, it is in St Cuthbert’s shrine in the cathedral. This is symbolised in the statue as being carried by St Cuthbert and the reason for Cuthbert not having a head is due to vandalism or iconoclasm during the Reformation when many statues across England were damaged and or removed. It was thought that people would worship a statue that they could see rather than God who could not be seen.

Above; Loretta’s drawing of Cuthbert’s Jewel found in his shrine. No photography is allowed. To see it, visit the museum in the “Monks’ Dormitory”.

Above; view of part of the cathedral known as the “Chapel of Nine Altars”.

Above; two of the altars are shown above, the central altar of St Aidan at the top and below, the altar of St Margaret of Scotland(1046-93). In the painting, she is accompanied by her son, the future King David I of Scotland.

Above; two photos of the tomb of John Neville. The top one has a green arrow pointing to his Neville family crest and the red arrow points to his wife’s family crest, Maud Percy. John’s father, Ralph, is buried nearby. John’s son, confusingly named Ralph Neville, was created Earl of Westmoreland in 1397 and helped to depose Richard II in favour of his brother in law, later known as Henry IV in 1399. References to him are made by Shakespeare in his plays Henry IV parts one and two. Ralph acted for Henry IV in suppressing an uprising of the powerful Percy family in 1403. His second marriage to Joan Beaufort produced nine son and five daughters. Ralph’s grandson was Richard Neville 16th Earl of Warwick aka the “Kingmaker” and his daughter, Cecily Neville, was the mother of Edward IV and Richard III.

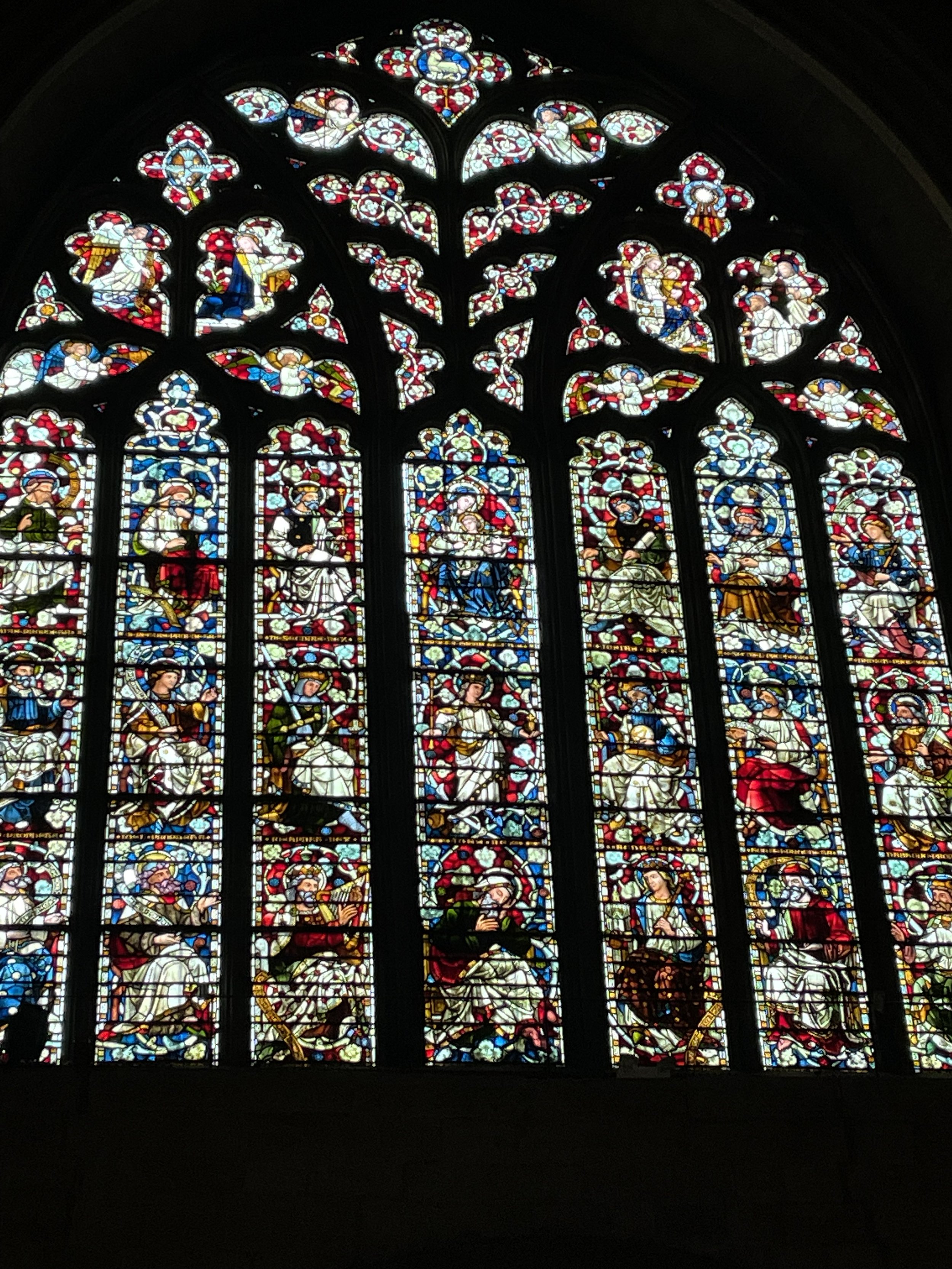

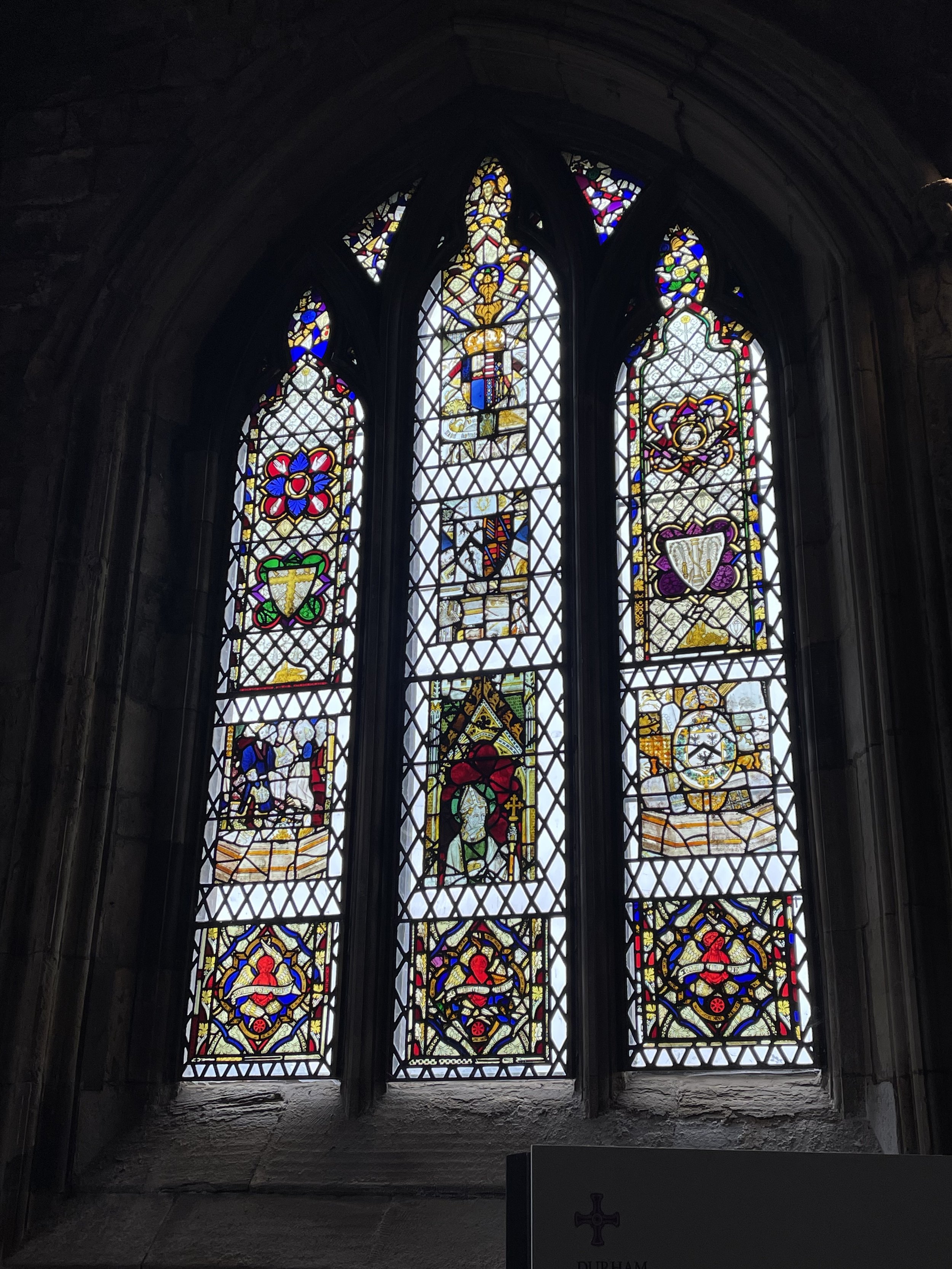

Above and the 3 below; Four of the beautiful windows in the cathedral.

Above; another beautiful window and a late 16th or early 17th century clock.

Above; the door to the cloisters with its medieval metalwork.

Below; the cloisters.

Above; the Norman doorway to the Chapter House, with a typical semi-circular arch and chevrons.

Below; the inside of the chapter house where all of the monastic business was discussed.

Above; a gravestone in the floor of the Chapter House of a Bishop of Durham.

Above and the next three below; Green Man ceiling bosses in the cloisters.

Below; the stunning and only surviving monastic dormitory in England. A small fee is charged to visit this place but it is well worth seeing. It was closed, being part of a monastery, in 1539 by Henry VIII and has now become a wonderful exhibition of Anglo-Saxon/Viking or “Early Medieval”, objects.

Above; several “hogback stones”. These are curved stones shaped a bit like Viking longhouses. They may be linked to graves but have not been found close to any bones. Professor Howard Williams has stated that they have all been moved and often reused in some kind of building work. They may have originally been grave stones or part of a stone memorial with a stone cross, simply being part of a bigger monument to possibly to commemorate a family. Typically, they feature a bear clasping something with a band over its mouth at each end and some decoration in the middle. This decoration can sometimes look like wooden roof tiles but it can also be an artistic design.

Some of these have been discovered in Scandanavia and so may be linked with the Vikings. It has been suggested that they are for key Vikings and reflect their high status, as well as their conversion to Christianity which commemorated the dead with stone headstones, crosses, etc.

Above; three more hogback stones.

Above and below; Early Medieval “Standing Crosses” .

Essential Information

Getting there.

Like many towns with a cathedral, parking is not easy but Durham has excellent “Park and Ride” carparks on the outskirts of the city. These provide a bus service into Durham where another bus can take you to the Cathedral. Bus drivers and passengers are so friendly in Durham that you can easily ask anyone for help.

Durham also has a train service. However, to then get to the Cathedral requires a catching a bus which has a very efficient service or a 15 minute walk which includes a steep hill.

Opening hours;

For up to date visiting hours click here.

Entry is free but they do ask for a voluntary contribution of £5 at time of writing this blog.

Facilities: Durham Cathedrals has one of the best cafes in the country. It may be crowded at lunchtime but it is well worth queueing. It also has toilets.

Articles that might interest you

A day’s wandering around this area of Coventry will present you with hundreds of years of history to discover. You will be able to visit the ruins of the 14th and 15th century church of St Michael that became a cathedral in 1918 as well as the new one next door.. About 160 metres away or a two minute walk, is Holy Trinity church with its amazing Medieval “Doom Painting” which some people believe is the best one in Britain. One minute away, is the wonderful and free Herbert Art Gallery and Museum.