The king in the car park part 1: Leicester Cathedral, Richard III's final resting place.

/In August 2012 there was a media frenzy taking place near an old car park in the city of Leicester. What was going on? The world’s media had just been informed that archaeologists had found skeletal remains which were possibly those of King Richard III of England. Back in August 1485, Richard III had been killed in the Battle of Bosworth Field by the army of Henry Tudor, soon to become Henry VII. There had been all kinds of theories about where Richard’s remains were and now, the current theory that he had been buried in GreyFriars’ Friary seemed to have been proven correct. Historian, John Ashdown-Hill was the latest historian to propose Greyfriars and Philippa Langley had taken up the challenge to test that theory. It took Philippa seven and a half years of research and action plans to create the “Looking for Richard Project” with a team of dedicated like minded people to discover Richard’s remains.

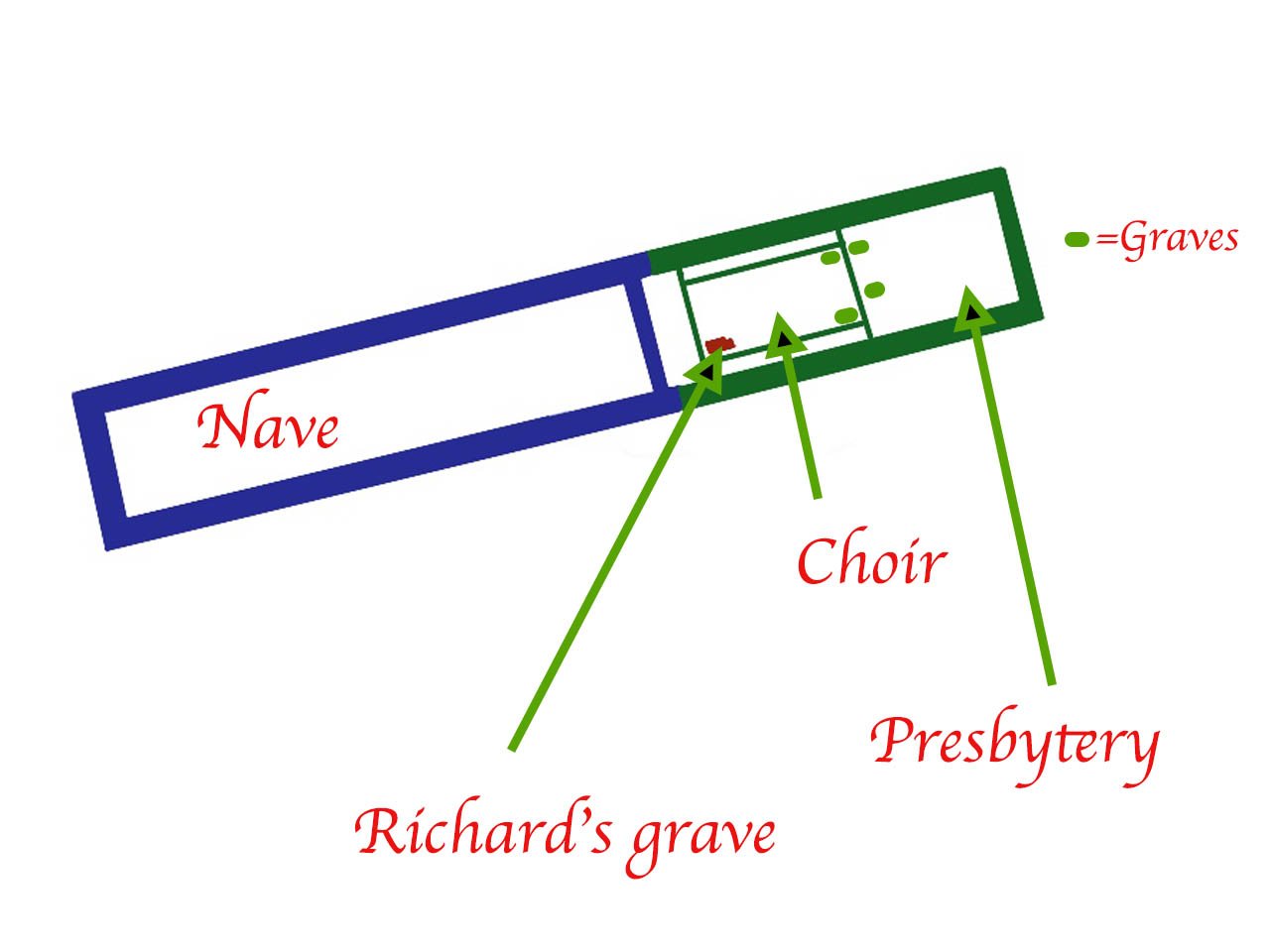

Next, she managed to convince Leicester City Council to give permission for a ground penetrating radar survey to assess the viability of a dig to excavate the northern end of the Leicester city Social Services car park. Unfortunately this revealed very little. She then raised thousands more pounds to finance the actual dig by Leicester University Archaeology Department and assess the findings. John Ashdown-Hill had predicted that the body would be found in the choir area of the church associated with the priory and others had then suggested where the church, with its choir, was actually located. However, lead archaeologist, Richard Buckley, had quietly told Philippa that the chances of finding the church were about fifty-fifty at best and nine to one against finding the grave!

Miraculously, two parallel legs bones were unearthed on the 25th August 2012, day one of the dig! These were initially covered over for protection whilst other areas of the trench were excavated but on the 4th September, very careful digging around the bones’ site began again, this time revealing a skeleton. Excitement soon began to develop amongst the archaeologists and Philippa’s team because the spine of the skeleton was S-shaped, suggesting that one shoulder might be higher than the other, something that had been linked to Richard III. There were also some possible battle injuries that could be seen in the skull. On the 12th of September 2012, the archaeologists announced that human remains had been found and were a possible candidate for Richard III’s body.

On the 4th February 2013, The University of Leicester confirmed that the human remains found in the car park were those of King Richard III. This was confirmed by mitochondrial DNA found in the body was matched with mitochondrial DNA in Michael Ibsen, Richard III’s cousin 14 times removed. (fully explained later).

What is there to see?

Above and below. The 2 tonne block of Swaledale fossil limestone quarried in Yorkshire with a the deep cross shape. The marble plinth comes from Kilkenny in Ireland. It is on an angle so that Richard faces the rising sun and suggests that Richard will rise to meet the risen Jesus. The standard christian practise is for christians to be buried with their feet towards the east, eventually to rise to meet Jesus on the day of his second coming.

Above.A closeup shot reveals the large amount of fossils in the stone.

The stained glass windows above and below are known as the “Redemption Windows” and were created by Thomas Denny. They are to be found in St. Katherine’s chapel only a few feet away from Richard III’s tomb. The windows show scenes inspired by the life of Richard which link to themes from the Bible.

Above. Two rose bushes symbolising the red rose of the House of Lancaster (eg ,Henry HVI and Henry VII) and the white rose of the House of York (eg Edward IV, Edward V one of the “Princes in the Tower”and Richard III). Below the roses are objects from history jumbled up over time.

Above. A panel showing Richard III ‘s naked body having been slung over a horse and taken after the battle to Leicester for all to see that the king was dead.

Above. A panel showing women surrounded by the bodies of their loved ones strewn across the battlefield.

Above In the middle panel is Jesus Christ sporting a 15th century haircut with other figures. On the left is the bottom of the panel seen earlier with the rose bushes. It shows more buried objects from history including a bishop’s crozier, a skeleton and a viking’s sword.

Above. Top left are two lovers riding past Middleham castle in Yorkshire, Richard III’s childhood home. Top right, are three children playing in front of a tower from Fotheringhay castle, the place where Richard was born.

Above. In the top left is a horse rider with a wild boar, Richard III’s emblem. Next to it are two symbols representing England, a castle and an English oak. Next to that is a scene from the Battle of Bosworth Field where Richard was killed and finally, Richard on horseback, wearing his crown and on his way to the battle. In the very far corner is a tower and out of frame in this photo is a football, symbolising Leicester City Football Club’s Premier League win in 2016. Unfortunately, I would have needed a ladder to get the football in the photograph!

Above and below are photos of Richard III’s pall ie a large cloth, often black, that covers the coffin in the funeral service. The coffin underneath the pall was made by Michael Ibsen, a man discovered by John Ashdown-Hill to be a descendent of Richard’s sister Anne. Michael’s mitochondrial DNA was used to prove that the bones discovered were those of Richard III.

The pall was created by Jacquie Binns and commissioned by Leicester Cathedral in 2013. Jacquie spent 12 months researching and preparing for the pall and 7 months making it.

In the photo above, the first 3 represent Leicester University with, from left to right; the university’s vice chancellor, Sir Robert Burgess; Richard Buckley, the lead archaeologist who is seen carrying a medieval floor tile from the dig and Jo Appleby, the osteology expert who is depicted carrying Richard’s skull. In the middle representing the city of Leicester, are Don Monteith, the Mayor, the Dean of Leicester Cathedral holding a Bible and Tim Stephens the Bishop of Leicester with his crozier. The last 3 are representatives from the Richard III society; Philippa Langley, the highly motivated lady who organised the funding and persuaded the archaeologists to “dig up the car park” : John Ashdown-Hill whose research and book inspired Philippa and suggested the precise location of Richard’s grave and Dr Phil Stone, chairman of the Richard III Society who is carrying a silver boar , the badge of Richard III.

In the bottom photo, the 3 people on the left are 3 anonymous people representing a mourner, a lady in a rich robe and a knight. In the middle are; Richard’s son, Edward, carrying a handkerchief indicate his ill health (he died before his parents); St Martin and Anne Neville,Richard’s queen. The last 3 are anonymous representatives of the church; a bishop, a Grey Friar holding a model of the church where Richard was originally buried and a priest holding a chalice.

How did Richard III die?

Richard III died in the Battle of Bosworth Field against the forces of Henry Tudor (aka Henry VII) on Monday August 22nd, 1485. He had a far larger army than Henry whose army was small but became smaller every time it was mentioned, to emphasise the miraculous nature of the Tudor victory. Henry’s army consisted of a mixed force of French and Welsh levies with hardly any Englishmen except for a few exiled English nobles. The battle began at 8am but early events were inconclusive. Everything changed however, when Richard “saw red” when he caught sight of Henry Tudor and decided to lead a charge directly at his opponent. His initial success climaxed with Richard cutting down the Tudor standard bearer and getting very close to Henry. Henry’s Foreign mercenaries responded by moving backwards to enclose Henry in a square formation of pikemen. It proved impossible for Richard to penetrate this wall of pikemen and when his charge came to an abrupt halt, men riding behind crashed straight into those who had stopped suddenly. There was total chaos as men fell off their horses whilst others crashed into them. At this precise moment, Lord Stanley who had taken a neutral stance at the beginning of the battle, now charged in with his army, to support Henry and take advantage of Richard’s disastrous attack. Stanley had been a loyal supporter of Richard but his wife, Margaret Beaufort, was Henry Tudor’s mother and so when the battle began, he was non committal waiting to see who was coming out on top before supporting the winning side. In the process, Richard’s horse was cut down and whilst falling to the ground, Richard’s helmet came off. This was followed by a blow to the head whilst he was trying to stand up and despite being offered a horse by one of his men, Richard refused and fought on, receiving several more blows to his unprotected head until one particular blow to the back of his head proved fatal. Allegedly, Richard’s dying words were, “treason, treason”. Richard’s leaderless army, many of whom had not actually done any fighting, now disintegrated and left the battlefield. The battle was over by 10 am, England now was under the Tudors.

What happened to Richard’s body?

It sounds awful but the normal practice at the end of a battle was for the dead to have all of their possessions including their clothes looted (by the time of the Battle of Waterloo, even teeth were extracted from the corpses to be sold to dentists to use as false teeth). Richard lll was no exception and his naked body, with a noose around his neck, was slung across the back of a horse. The noose was used to drag his body off the battlefield. Armies did not come with body bags or coffins and so the treatment of Richard’s body was not unexpected although the Crowland Chronicle describes the body being carried back to Leicester “with insufficient humanity”.

Whether he was buried with a ceremony befitting a king will never be known. He was buried at the Franciscan Friary at Greyfriars, Leicester and there is evidence that the friars had a reputation for carefully carrying out their religious duties. Furthermore, the Leicester Friars had shown that they favoured the Yorkists in earlier times by opposing the accession of Lancastrian Henry IV to the extent that two were hanged as a result. They had benefitted from the patronage of the Yorkists but the Lancastrians were back in power. This suggests they did what they could but as Henry VII had the last word in what should happen to Richard’s body we are, again, unsure as to what did happen. According to John Ashdown-Hill, when Richard’s grave was excavated, archaeologists discovered evidence that suggest the burial was done in a rush and without ceremony . In the journal Antiquity, the archaeologists state;

“The body appears to have been placed in the grave with minimal reverence. Although the lower limbs are fully extended and the hands lay on the pelvis, the torso is twisted to the north and the head, abnormally, is propped up against the north-west corner of the grave. Irregular in construction, the grave is noticeably too short for the body. Unlike other graves in the choir and presbytery in Trench 3, which were of the correct length and neatly rectangular with vertical sides, this grave was an untidy lozenge shape with a concave base and sloping sides, leaving the bottom of the grave much smaller than its extent at ground level.”

There was no evidence of a coffin or shroud, something the friars would not have omitted. A shroud would have bundled up the limbs, something not seen in this grave. A coffin would have left coffin nails in the soil but none from this period were found. The article in Antiquity also states:

It is possible that Henry VII’s officials quickly dug a simple pit in the choir part of the church, thrust the body into it and covered it over with soil! Even then, it is believed that the friars would have conducted some kind of religious ceremony.

The most high status part of the church was the “presbytery” and this was usually where important people were buried, especially being visible to the Friars attending their regular services. The choir, on the other hand, was less accessible to any of the laity (non friars) attending a service and thus keeping Richard out of the public eye and reducing the possibility of any veneration of Richard in years to come.

The Antiquity article also concludes;

“The final arrangement suggests Richard III’s body was lowered feet first, torso and head second. This would account for the neat extended position of the legs and the manner in which the upper torso and head were partially propped up against the grave side. This was because the bottom of the grave was too short. That no effort was made to rearrange the corpse, once again, implies haste. Even moving the body to the centre of the grave would have allowed the torso and head to be straightened and the body to be arranged more carefully. The haste may partially be explained by the fact that Richard’s damaged body had already been on public display for several days in the height of summer, and was thus, in poor condition. ”

In 1495, Henry VII ordered that Richard III should have an appropriate tomb made from alabaster. This followed the practice where the overthrown king, Henry VI, was reburied at Windsor, 12 years after his death and the overthrown Richard II was given a burial befitting his position, 14 years after his initial internment. It is thought that the tomb even had an effigy or image of Richard on the top. There it stayed, centrally located in the choir church of Greyfriars Friary for the next 43 years. Why did Henry do it? Probably to win Yorkist support at a time when his throne had been challenged by the Earl of Lincoln and a man called Lambert Simnel, who claimed to be be Edward Plantagenet, 17th Earl of Warwick, son of George Plantagenet, 1st Duke of Clarence, Richard’s executed elder brother.

How did Richard’s body become lost?

Moving forward to the reign of Henry VIII, having just split with the Church of Rome, he found that a lot of monks, nuns and friars did not agree with his law that he, not the Pope, was the head of the Church of England. He was also short of money and thus his plan to shut down (dissolve) all the monasteries, friaries, priories etc, would stop this religious opposition and also provide him with a huge amount of land and other possessions, to sell. The greyfriars were expelled from the friary in 1538 and their land was sold. Friary buildings were destroyed and building stone was stolen but the graves were left . Across the country, relatives of people buried on monastic land attempted to rescue their remains and rebury them but in Richard’s case, having no near relatives, he was simply left where he was buried. Over time, the materials that made up his tomb were also stolen leaving his grave to blend in with the surroundings.

The friary land was bought Robert Herrick, a former mayor of Leicester who built a house for his family and created a garden where the priory church once stood. The story then takes an odd twist with Christopher Wren, the father of the man who later designed St Paul’s Cathedral after the Great Fire of London (1665) was visiting the Herrick family to tutor Robert’s nephew. On one of his visits, he noticed that Herrick had erected in the garden, a 3 foot pillar bearing the inscription, “Here lies the body of Richard III, one time king of England”. Although Wren apparently made a note of the monument when he got home, the pillar disappeared and the garden eventually became a car park.

Misleading accounts led to myths about the whereabouts of Richard’s body

In 1611 John Speede wrote that Richard’s tomb was completely destroyed with his remains being dug up and buried at one end of “Bow Bridge”. Apparently he failed to support his story with any evidence other than from local oral accounts that had been passed down over time. John Ashdown-Hill checked out this story and concluded that;

“it is very difficult to see how any burial would have been possible under the low stone arches of the old Bow Bridge”.”

Over time, this account was altered to the extent that Richard’s body was dug up and dragged through the streets of Leicester by a “jeering mob” and then thrown into the River Soar near Bow Bridge. Again, there was no evidence for this version either. Ashdown-Hill argued that few people in Leicester knew this story either and that there were no recorded examples of this happening to burials at the time of the dissolution of the monasteries anywhere in the UK. He went on to state that he has not seen any evidence for the people of Leicester disliking Richard III to the extent that they would carry out such action. Added to this was that during the 18th century, people came to refer to the existence of an old stone coffin which was used for a horse trough as Richard’s . Throwing the body into the river could the explain why the coffin was empty. In the 19th century a commemorative stone plaque was erected and a damaged skull was found in the River Soar that had marks that could have been caused by a sword!

Speede also managed to get the location of the Grey Friar’s Priory (Franciscan Friars) wrong by confusing it with the location of Leicester’s Blackfriars’ Friary, (Dominican Friars) a completely different friary for completely different friars! The Blackfriars were based to the north west of today’s Leicester Cathedral whereas the Greyfriars were based to the south. To make things worse, Speede didn’t even label the Greyfriar’s location on his map! This large error would have misled people looking for Richard’s grave for hundreds of years.

How were the remains proven to be Richard III?

Richard’s body was identified by discovering a mitochondrial match between his remains and that of Michael Ibsen his distant cousin. Mitochondrial DNA can be found in a variety of cells in skeletons and so there was a good chance of discovering some in Richard’s remains. Mitochondrial DNA is passed down through female ancestors. Mothers pass it down to all of their children, boys and girls but only girls pass it on to the next generation. As it can only be passed down from one generation to another in human eggs and men don’t have any eggs, it is only passed on by women. If there are no female children in a family, that family cannot pass it on any further down the line. Obviously, Richard could not pass it on but his sister could and so John Ashdown-Hill researched Richard’s family tree but only going down the female line. Richard’s sister, Anne of York had the same Mitochondrial DNA as Richard and so her lineage was followed all the way down the female line, ending up with a lady called Joy Ibsen and her son Michael Ibsen. Loads of times a female line would come to an end and so other lines had to be pursued but eventually John Ashdown-Hill managed to find that female line. To be absolutely certain, Leicester University did similar research to John Ashdown-Hill and found another complete female line to a lady called Wendy Duldig. Their mitochondrial DNA matched each other and they also matched Richard’s remains. Their direct female lines both began with Richard’s elder sister Anne of York but after two generations split into two distinct but direct female lines.

Scientists could also do a trace through the Y chromasone in males but to be successful, every father in a tree has to be a biological father but in Richard’s case, someone must not have been the biological father of his so called son! Somewhere in the 19 generations, someone was not a real biological father and therefore people who were thought to be his living descendants through family trees, were not. Apparently, this occurs according to research in about 1-2 percent of the male lines. Historically, a break in the line could mean that royal descent was incorrect. That is to say, if Edward III was not John of Gaunt’s biological father, none of the House of Lancaster via Henry IV or the Tudors really had a legal claim of descent. Likewise, if Edward III was not the biological father of Edmund Duke of York, none of the Yorkist claims ie Edward IV, Edward V or Richard III were legal! Unfortunately, we will never know the answer to these fascinating questions.

Interestingly, as there are no contemporary paintings of Richard, DNA can also tell Richard’s eye and hair colour. He turned out to have blue eyes and as a toddler, had blond hair which would have turned darker as he reached adulthood.

When DNA is put alongside all the other evidence it turns out that Leicester University is 99.999% certain that the remains are Richard III’s. That evidence being, the battle wounds, the age of the skeleton being similar to Richards, the date given to the remains being the end of the fifteenth century, the location of the body and how it was buried ie done in a rush with little concern or respect as well as the DNA evidence.

Shakespeare’s play, Richard III portrays Richard III as an evil villain with associated hunchback and horrible demeanour.

On their website Shakespeare Birthplace Trust write;

“‘Child killer’, ‘murderer’, ‘usurper’ are all phrases you would associate with Shakespeare’s greatest villain - Richard III. Thanks largely due to the Shakespearian portrayal, Richard has gone down in history as one of England’s most evil monarchs. So, was the real Richard III truly as monstrous as Shakespeare made him out to be? Well the short answer is no.”

This portrayal of Richard in the play, being widely performed all over the world and for 400 years, served to add spice to the mystery of the apparent disappearance of Richard’s body. “Child killer” refers to the unexplained disappearance of Edward IV’s two young sons whilst living in the Tower of London during Richard III’s reign. Just days before Edward V’s coronation, he and his brother, Richard Duke of York were both declared illegitimate and thus, neither could not take up the throne of England, leaving the way for their (“wicked”) uncle to become king in their place. The character of Richard III is given a hunchback, a withered arm and sometimes a limp as well as an evil sounding voice, a pantomime villain but without any humour. A monstrous king who will stop at nothing to achieve his aims. Put all this in the mix and the mystery of Richard’s remains becomes a quest for many to finally solve.

Did Richard have a hunchback?

Prior to his body being discovered, the Richard III Society proclaimed that Richard was not a hunchback because he would have not been able to wear a full suit of armour and go into battle if he had such an impediment. If you watch any of the documentaries about the body’s discovery, Philippa Langley who led the pursuit of Richard’s grave was distraught when the curved spine was revealed to her. In her mind it was a certainty that Richard was not a hunchback and the hunchback claim was simply evil Tudor propaganda to blacken his name. However, historian Julian Humphrys writes;

“Although this was a scoliosis (sideways curvature of the spine) rather than a kyphosis (a true hunched back) and it’s been proved that it wouldn’t have prevented him from charging into battle, it’s thought that one of Richard’s shoulders would have been noticeably higher than the other.”

Along with a visit to Richard’s tomb in Leicester Cathedral, we strongly recommend a visit to the Richard III Visitor Centre next door. You can actually see his grave!

Click here to visit our Richard III Visitor Centre blog

Essential information.

Getting there;

By car sat nav LE1 5PZ

FROM THE SOUTH:

Leicester is located just off the M1. Exit the M1 at Junction 21, signposted M69 and Leicester. Follow signs for A5460 heading towards Leicester City Centre. Follow for approximately 3 miles and follow signs for Castle Gardens and Highcross. Arrive at St Nicholas Circle and take the 3rd exit off the St Nicholas Circle roundabout, onto Peacock Lane. Leicester Cathedral is located on your left, next to St Martins House Conference Centre.

FROM THE NORTH:

Leicester is located just off the M1. Exit the M1 at Junction 22 and join the A50. Follow the A50 for approximately 8 miles, then follow signs for Vaughan Way then follow signs for the A47. You will arrive at a junction with Highcross straight ahead. Take the left lane to avoid the underpass which leads up to St Nicholas Circle and the Holiday Inn hotel. Take the left lane and follow onto Peacock Lane. Leicester Cathedral is located on your left, next to St Martins House Conference Centre.

Parking

Long-stay car parks are available nearby at St Nicholas Circle NCP (next to the Holiday Inn, postcode LE1 4LF) and at the Highcross Shopping Centre (accessible from Vaughan Way, postcode LE1 4QJ).

New Street Car Park

The New Street car park (a facility managed by our partners at St Martins House) has now reopened following resurfacing. At present, parking on Monday to Friday is restricted to permit holders only, but on Saturdays and Sundays it is open from 7am to 6pm at the following rates payable by debit card or chip and pin only – no cash. This is in order to protect our staff.

By train

There are good rail links to Leicester from Birmingham, Sheffield and London. Cathedral Gardens and St Martins House are a 10–15 minute walk from Leicester city rail station, turning right out of the exit along Granby Street and Gallowtree Gate, before turning left at the Clock Tower along Silver Street.

By bus

For information on bus services in Leicester, please visit the City Council website: http://www.leicester.gov.uk/transport-and-streets/travelling-by-bus/

For further information on bus services throughout Leicester and Leicestershire, including Park & Ride services, call the Travel Line on: 0871 200 22 33.

Entrance fees;

At the time of writing, entrance is free but a voluntary donation is encouraged.

A day’s wandering around this area of Coventry will present you with hundreds of years of history to discover. You will be able to visit the ruins of the 14th and 15th century church of St Michael that became a cathedral in 1918 as well as the new one next door.. About 160 metres away or a two minute walk, is Holy Trinity church with its amazing Medieval “Doom Painting” which some people believe is the best one in Britain. One minute away, is the wonderful and free Herbert Art Gallery and Museum.